(Cairncross Collection, Ivey Family London Room, London Public Library)

Originally published in Maclean’s Magazine, May 28, 1955.

A MACLEAN’S FLASHBACK

By Stanley Fillmore

Almost Every Home In London, Ontario, Was Draped In Mourning When The Bodies Of a Hundred And Eighty-One Victoria Day Excursionists Formed The Final Link In An Incredible Chain Of Blundering Irresponsibility.

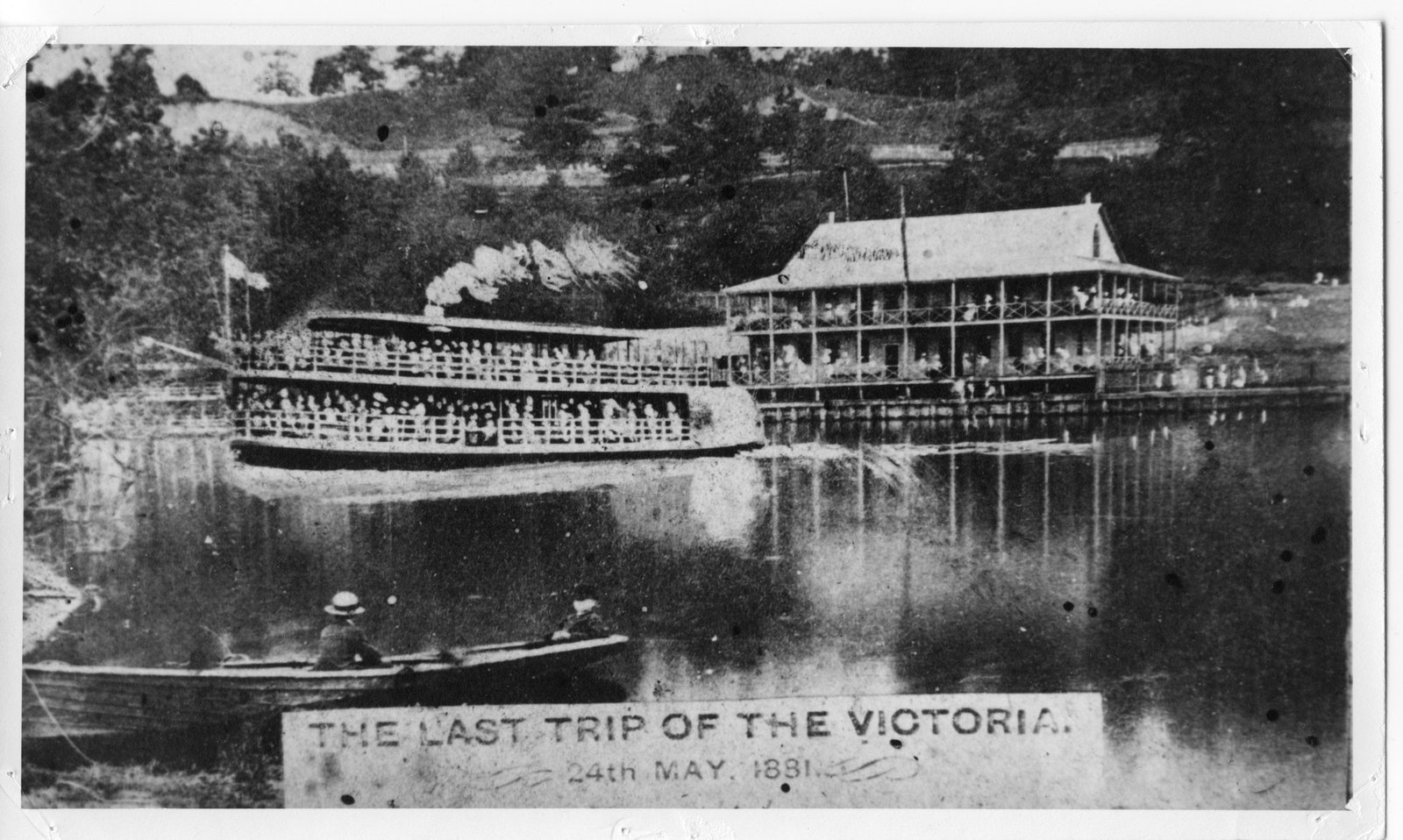

On a sparkling Tuesday in May 1881, while Queen Victoria was celebrating her sixty- second birthday in London, England, a steamboat, also named VICTORIA, was cruising

on the Thames River near London, Ontario, crowded with more than six hundred exuberant excursionists. Suddenly, something happened.

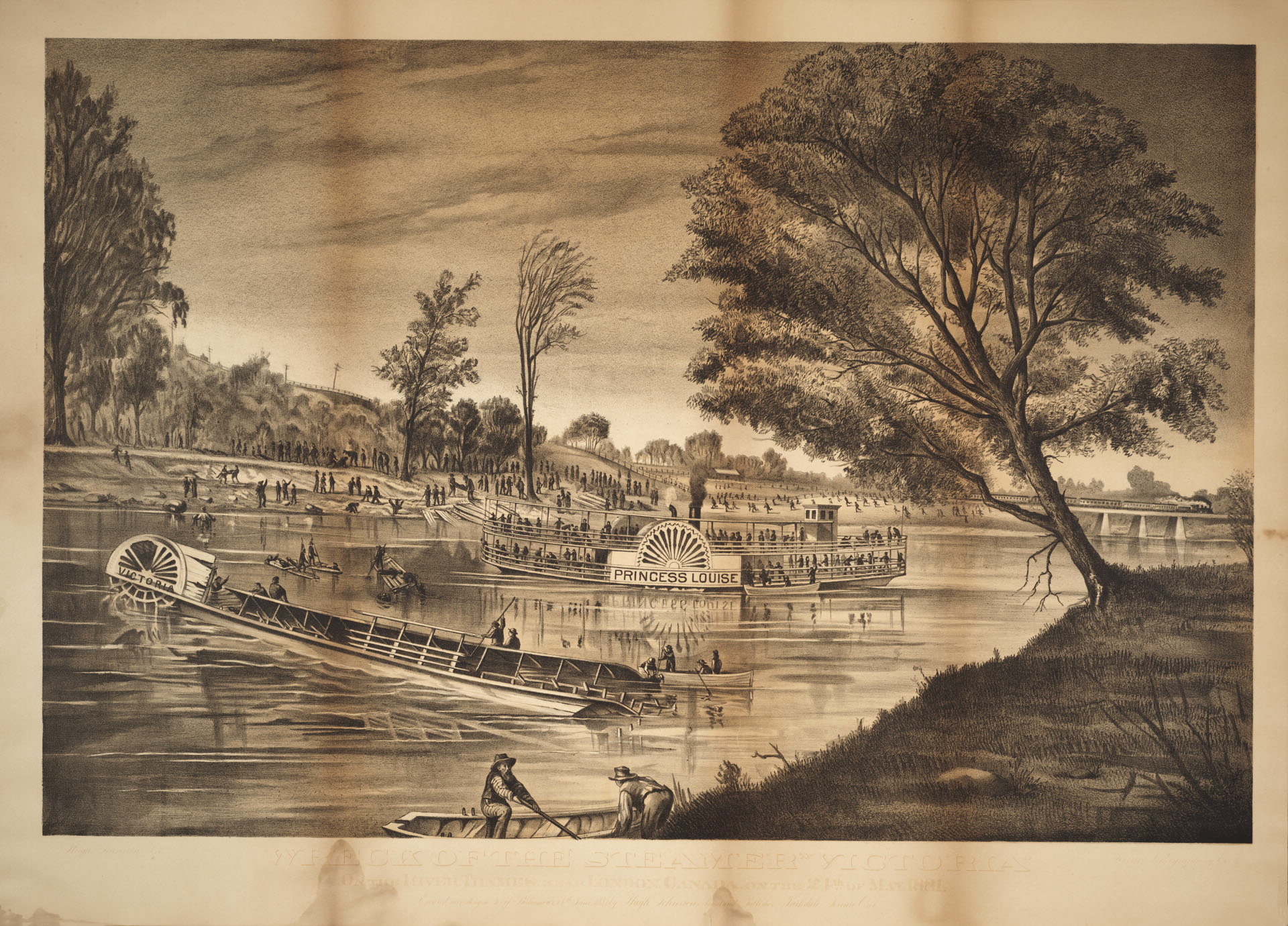

From his seat in a racing skiff less than a hundred yards off the VICTORIA’s starboard bow, Harry Nicholls watched the boat wallow toward London. He saw her rock ponderously from side to side responding to the motion of the upper-deck passengers who were running from rail to rail. The unusual swaying did not startle Nicholls who was aware of the VICTORIA’s shallow draft, but as he watched he saw the rocking increase until inches of water were shipped at each swing. Suddenly, with a roar of hissing steam, the boat’s huge boiler broke loose from its mounting and crashed through the bulwarks. Water poured through the opening and Nicholls was enwrapped in a cloud of live steam. With a slow, almost deliberate, movement the VICTORIA settled on her side. From both decks passengers were catapulted into the river. Nicholls heard the muffled screams of those trapped between decks. His slim shell was almost swamped in the wake as the VICTORIA went down.

At least a hundred and eighty-one persons drowned on the May 24 excursion; of these, a hundred and ten were children. It was the blackest day in London’s history, the result of an almost incredible series of blunders that could easily have been averted.

By nightfall the flags that bedecked London homes and businesses to mark the Queen’s birthday were lowered to half-mast. For eight days afterward, the dead who had been hooked from the river were carried to their graves. Funeral directors started work before dawn and were still conducting services long after dark. The supply of coffins in London was exhausted the first day and one infant was buried in an adult casket.

All London’s nineteen thousand residents lost relatives or friends. One family, the Fryers, lost five members. By official decree a black armband became a Londoner’s badge of mourning for a thirty-day period. Business firms and schools closed for two days. Most homes in the city were draped in mourning. One milliner advertised in the London Advertiser: “Family mournings at A. B. Powell and Co. who are showing a large range of crapes and mourning-dress material. Our prices are low. Millinery orders executed at the shortest possible notice. Also dressmaking orders.” Draymen charged double their usual funeral rates.

The tragedy had its start in the fall of 1880 when George Parish, London secondhand merchant and moneylender, assumed control of the VICTORIA. Parish had supplied the capital for Captain Thomas Wastie to build her seven months earlier and the vessel was returned to Parish in lieu of mortgage payment when Wastie moved from London.

Parish planned to use the VICTORIA as an excursion boat on the Thames between London and Springbank Park, four miles downstream. The 73-acre park with its landscaped grounds, refreshment booth and tavern was London’s favorite picnic and play area.

In a deal with the Thames Navigation Company, Parish agreed to supply the 400-passenger VICTORIA and his services as manager in return for a one-third split of the summer’s profit. On its part, the company was to put up its two boats, the FOREST CITY, a side-wheeler of 150-passenger capacity, and the PRINCESS LOUISE, another side-wheeler carrying three hundred and fifty. The boats were to sail from the London dock at hourly intervals. A fifteen-cent ticket for the round trip entitled passengers to pick their own time and boat.

Square on both ends, the VICTORIA was seventy-nine feet, six inches long, twenty-six feet in the beam and drew a scant two and a half feet of water. She had two decks. A glass wheelhouse occupied part of the upper deck. Parish had installed a new steel-plated boiler aft of the broad staircase connecting the decks. It was ten feet long, three and a half feet in diameter and had ninety pipes inside as heating coils. It delivered sixty horsepower to the two stern wheels. Stacked beside the boiler was cordwood fuel. Parish had hired as captain Donald Rankin, a solid, mustached Londoner of forty-eight. Disaster struck the first day she sailed on the Thames River.

Spanking white, the VICTORIA glided easily on her course on the first trip of that fateful May 24, 1881. Sailing time was 9 a.m. The crowd aboard was gay and laughing. Children ran wildly about the decks, shouting at farmers working along the shore and startling placid cows drinking at the river’s edge. As she slipped into the dogleg turn under the Great Western Railway bridge a mile from the city, the passengers waved at travelers aboard a Windsor-bound train.

Another mile downstream the boat put into the Woodland Cemetery dock where several people disembarked to tend relatives’ graves. Another mile and the VICTORIA stopped at Ward’s Hotel where London’s young sporting bloods gathered to enjoy cock fighting and drinking. At this time of day, however, the only passengers who got off were a few tavern employees who used the boat for commuting. The VICTORIA continued to the Springbank landing stage where Captain Rankin eased her into the jetty. When her passengers went ashore the VICTORIA returned to London for another load.

Twice more she made the same round trip without incident. But then, at 3.30 p.m., as she was putting into the mooring basin at the London docks to stand by for her scheduled loading at five o’clock, Rankin saw the FOREST CITY smallest of the three-boat excursion fleet, aground on a shoal in midstream. The third boat, the PRINCESS LOUISE, was straining at the FOREST CITY with lines but she refused to budge.

Skirting the sand bar and the two ships, Rankin brought the VICTORIA into the dock. Coming out of his wheelhouse, he shouted to the FOREST CITY’s skipper to ask how long the boat had been mired. “She struck just after loading at three o’clock as we were backing away from the dock,” the captain replied. “The PRINCESS LOUISE will stay to help float us free.”

The information upset Rankin. The three craft had carried thousands to the park. As yet, at almost 4:30 p.m. few had given a thought to returning. Now, with one boat grounded and a second trying to pull her free, the burden of taking the swollen crowds back to London would fall to the VICTORIA alone. At that moment Rankin was acutely aware his ship was constructed and licensed to carry no more than four hundred passengers.

Instead of waiting for the scheduled 5 p.m. sailing he decided to cast off immediately. He first persuaded the skipper of the PRINCESS LOUISE to agree to follow him to Springbank instead of staying with the FOREST CITY.

As the Victoria docked at Springbank several youths leaped from the landing and scrambled over the bulwarks. Then hundreds rushed aboard. Many had been patronizing the park’s tavern. Rankin saw the crowd was not only large but rowdy. He assembled his six man crew and instructed them: “Walk about and tell people we are overcrowded. Tell them the captain will not sail until many of them leave the boat. There will be more trips coming and all of them will get rides to London if they wait.”

“Not more than fifteen or twenty obeyed my commands,” Rankin reported later. From the dock george Parish, the cruise manager, was signaling him to take the boat out. Packed to the gunwales with more than six hundred men, women and children, the VICTORIA left the Springbank dock.

In its natural state the Thames had been a meandering stream nowhere wider than seventy-five feet nor deeper than five. Steamboat navigation had been made possible when a dam was built across the Thames at Springbank in 1879, raising the water level. Londoners recalled the harmless stream and scoffed at suggestions that the deepened river could be dangerous. When the Victoria went into service Londoners joked that the job of a farmer’s son hired as a crew member was to shoo drinking cattle from the course. Other wits claimed the boat had once grounded herself while attempting to pass over a tin can lying on the river bed.

John Drennan, a reporter for the London Advertiser, was standing on the VICTORIA’s lower deck on her last voyage. “I don’t like the way the boat is rocking,” Drennan heard a young father with two small daughters by the hand complain to a friend. “What does it matter?” the friend asked. “If the boat capsizes, we can walk to shore even those two young ones of yours. Minutes later, Drennan saw the father, one of his daughters and the friend disappear into twelve feet of water.

As the Victoria nosed out of Springbank under half steam, she was taking small rivulets of water over her lower deck but otherwise holding a reasonably steady course. Since she was already loaded past the danger point, Captain Rankin refused to put in at Ward’s Hotel where several would-be patrons waited. He also refused to stop at Woodland Cemetery.

The Boiler Broke Loose

Just past Woodland high-spirited youths on the upper deck started running from side to side. As more passengers took up the amusement the boat rocked ponderously, swinging farther and farther with each surge. At the end of each swing water gushed over the lower deck and passengers scrambled to the opposite side to avoid wet feet.

In his wheelhouse Rankin was terrified. Two hundred yards upstream the river took a sharp turn north under the Great Western Railway bridge and the current at the spot had thrown a sand spit into the stream. Rankin steered the ship toward the spit, determined to ground his boat and order the passengers off. The steamer was starting to respond when he felt a jar as if the bottom had scraped.

At the same moment the crowd noticed two racing shells off the starboard bow and swarmed to the starboard rail to watch them. The VICTORIA dipped sharply enough to frighten her passengers, who tried to right her by pressing to her port side. Their weight overbalanced her and she toppled port side down. The cant of the lower deck dislodged the boiler. It crashed through the bulwarks opening a hole through which water poured by the ton. Steam scalded several on the spot. The pine stanchions supporting the upper deck crumpled and the whole superstructure collapsed, trapping the crowd on the lower level. It was 6 p.m.

Until the moment of the disaster, not more than a handful of the six hundred passengers had a premonition of danger. One of those who could sense death in the air was Benjamin Eilber, a fourteen-year-old London schoolboy who had saved fifteen cents from his allowance for his excursion fare. Eilber survived the wreck and is still actively managing his own general store in Ubly, Mich., at the age of eighty-seven.

“I was riding on the upper deck when the boat started to rock,” he recalls.

“Some of the passengers thought the rolling motion was great fun; they even started to sing One More River to Cross. I went down to the lower deck so that if the worst came I would be nearer the water and could swim. I was standing beside the pile of cordwood fuel talking to a policeman and after several bad lurches we decided to swim for shore. As soon as we were in the water the boat took a violent lurch and started to go down. The policeman and I were far enough away by this time that we were not trapped in the falling wreckage.”

Eilber was a poor swimmer and barely made the seventy-five yards to land. He and the policeman gathered boards lying along the bank and flung them into the water to assist those struggling to shore. Eilber and a young friend started into the city with news of the disaster.

Some of the first survivors ashore were met by the farmer on whose field they landed. Unfeelingly he ordered them from his land, But his bluster soon faded when John Mitcheltree, a strapping butcher, coolly surveyed him, called for a coil of rope and cast his eye about for a convenient branch to hang it from.

At the time of the disaster, Frank Moore was driving a horse-drawn hack to London along the banks of the Thames. His passenger was John (later Sir John) Carling, London MP and founder of the Carling Brewing and Malting Company, who had spent the afternoon at Springbank. Moore later recalled: “We saw the VICTORIA on its way to the London wharf. There was a great merry crowd aboard and we could hear them laughing and singing and having a gay time generally.

“We lost sight of the boat — just for a couple of minutes or so. There was a rise-a kind of hump in the contour of the land-that obstructed our view. And while we were driving around it we heard the most fearful, sudden, terrible wails and cries and shouts. It rings in my ears; the day was so beautiful and everything was so happy and all holiday-like, and then came those awful wails.”

On Carling’s instructions, Moore ran the hack close to the riverbank. “The victims were fighting like mad things,” Moore remembered. “The worst thing was to see mothers and fathers trying to reach down and pull up their children who had been crowded under and were drowning. Then the parents beat and pulled each other down. They were walking-yes, walking-on each other!” Moore attributed the heavy loss of life to the fantastic scramble.

Carling and the hack driver helped many survivors ashore. At Carling’s suggestion Moore used the hack to carry several women to their homes. Moore drove to the city so fast that one of his two horses died that night.

Two sisters who had made the excursion cruise alone, nine-year-old Henrietta and twelve-year-old Mabel Hogan, were hurled from the upper deck into the water. Mabel sank immediately. Henrietta lunged and grasped her by a ribbon about her throat, but the child was stunned and could do nothing to support herself. She sank again before her sister’s eyes. A priest returned the hysterical youngster, still clutching the sodden ribbon, to her parents. The boat’s pursers, Alfred Wastie and Herbert Parish, sixteen-year-old sons of the builder and the cruise manager, perished in the wreck.

By 6.30, news of the disaster had reached the city and started a stampede to the scene. One of the first to reach the river was a robust butcher, John Courtis, who worked in a shop near the London wharf. Courtis threw off his shoes and shirt and waded into the water, scooping up bodies of victims and carting them ashore. Many of the ship’s passengers had saved themselves by clinging to the wreck of the VICTORIA until some of the congestion in the water cleared. Courtis helped many of these ashore. While he pulled the bodies of friends and acquaintances from the river, Courtis was spared the horror of finding one of his own family but was himself a victim of the VICTORIA; the exertions of his work coupled with the cold water gave him pneumonia and he died two weeks later.

Searching the Rows of Dead

Five minutes after the VICTORIA overturned, the PRINCESS LOUISE, which had followed her to Springbank, came in sight. Her captain ran her ashore and discharged his load: – The PRINCESS LOUISE was turned into a floating morgue and by 10 p.m. a hundred and fifty-seven bodies were removed from the river and placed aboard. It was an eerie scene with petroleum-soaked torches and huge bonfires throwing grotesque shadows as workers toiled to load the gruesome cargo. Police Chief W. T. T. Wiliams had mounted a three-man detail on the morgue boat to prevent looting or removal of bodies before identification could be made.

John Mustil, a blacksmith of immense build, searched the riverbank in vain for the body of his thirteen-year-old daughter, Priscilla. Now he mounted the gangway of the PRINCESS LOUISE to look for her there. He thrust aside constable William Hodge and searched the rows of dead. He found her lying beside the body of an old man whose arm had fallen loosely about her neck. Tenderly, Mustill lifted the child’s body to his arms and walked from the boat.

Another frantic parent was Jake Brown, a piano tuner. That morning his twelve-year-old son John had begged to be allowed to spend the day at the park. Against his better judgment Brown had sent the boy off with a picnic lunch under his arm. Brown hurled himself into the recovery work and rushed to see each body as it was retrieved from the water; John was not to be found. Throughout the night Brown stayed, whipping his tired body to work.

At dawn he returned home and was pouring out his grief to his wife when the boy walked in, dirty, disheveled, but showing no sign of having been in the water. When taut nerves calmed, the story came out: as he set out that morning, the boy had changed his mind, decided to go by train to Port Stanley, had missed the last train home and had walked the entire twenty-five miles to London.

While retrieving of bodies proceeded, many of the rescued found themselves re-living the incidents leading to the disaster. Most agreed that had the upper-deck crowd not seen the rowing race, the tragedy might have been averted.

Harry Nicholls and Michael Reidy, the unwitting triggers of that final rocking of the VICTORIA, were ardent oarsmen, both members of the Forest City Rowing Club. During the afternoon of May 24 they had been practicing on the stretch of river between the clubhouse dock adjoining the London steamer wharf, and Springbank. Most of the afternoon’s rowing had been routine training but occasionally they would stage impromptu races. They were heading for the clubhouse when the VICTORIA wobbled up just at six o’clock. “Let’s give them a race, Reidy shouted and the two shells streaked upstream. The two scullers were horrified as they watched the VICTORIA heel over and collapse. They swung their shells around and glided close to the wreck. Each man pulled survivors into his light craft and stroked for shore. More than fifteen were saved in this manner.

A Second Son Drowned

Those passengers who were thrown clear had the best chance to save them selves. John Fitzpatrick, a railway baggageman, saved his wife, daughter and baby granddaughter by taking a woman under each arm, grasping the baby’s clothes in his teeth and then floating and flutter-kicking his way to shore. A five-year-old girl saved herself by grabbing hold of Thomas Atwood’s long white beard and being towed to safety.

The collapse of the boat was a complete surprise to James Perkins. Listening to the chatter of his eight-year-old son, Jimmy, Perkins was caught off guard. He and his son were thrown from their lower-deck seats and were separated in the water. Perkins saw a boy he thought was his son bobbing about several feet from him. An excellent swimmer, he reached the boy in two strokes. Grabbing the child under the chin, he fought his way to shore. Pulling the lad up the bank, he laid him on the grass and screamed in anguish; he had rescued the wrong boy. Jimmy, whose body was not found until two days later, was the second son Perkins had lost in drowning accidents. Two years earlier an older boy had perished.

The PRINCESS LOUISE returned to London at 10 p.m. with her cargo of a hundred and fifty-seven dead. Men worked on through the night and another eighteen bodies had been re covered by eight o’clock the following morning. Another four were pulled to the surface that day. Artillery pieces from the London Field Battery were fired over the wreck in the belief that explosions would raise sunken bodies. The experiment was a failure.

During the next five days rowboats with grappling hooks and pike poles probed the river depths for more victime; the Springbank dam was opened to lower the water and help the search. Two more bodies were brought ashore. The total reached a hundred and eighty-one. A medical student, writing to a London paper, hotly denied the rumor that students had stolen bodies for dissection.

On May 25, London began to bury her dead. A note in the London Free Press told of hackmen raising their customary rates, of liverymen charging five dollars for one and a half hours service and of draymen demanding “all sort of exorbitant fees, at least one getting as high as ten dollars for two hours.” One wagon owner hit on a grisly C.O.D. plan. He spent May 25 hauling from the disaster scene bodies of victims he recognized. When he delivered the body to the victim’s family, he would claim a fee. In one instance he drew up in front of a victim’s home to find that the family was absent at the river, searching their son. Undismayed, the wagon driver lifted the body from his cart, pushed it through an open window and left.

The funerals of twenty-three-year-old Willie Glass and his nineteen-year-old sweetheart, Fanny Cooper, were held from the separate homes but blended into one procession on the way to the cemetery. The young couple were to have been married two weeks from the day of the wreck. Today in Mount Pleasant Cemetery they rest in adjoining graves. A single headstone supporting a tall pillared arch covers the graves. The inscription, “They were lovely in their lives,” begins on one pillar and continues, “and in death they were not divided,” on the other.

A hastily formed citizens’ committee met on May 25 to plan a suitable memorial. John Carling and John Labatt, also a brewer, were members. First plans favored a stone monument in a city park but the apparent need of many families whose breadwinners had died in the disaster wrote an end to this. One committee member commented, “The families of the victims are crying for bread. How ridiculous to offer them a stone!”

Some months later a subscription, taken among the parents who lost children in the disaster, raised a sum to erect a small brick building on the grounds of the Protestant Orphans’ Home in north London. For fifty years the cottage was used by the orphanage as an infirmary and school. A lintel stone above the front door carried the simple inscription: “In Memoriam, May, 1881.” Twenty years ago, when the orphanage sold some of its property, the cottage was razed. Today the only public monument to the disaster is a small cairn erected in 1916 by the London and Middlesex Historical Society at the site of the sinking.

Public outcry and official reaction to the tragedy condemned the FOREST CITY. Her rotting hulk lies on the river bed at the old landing stage in Springbank Park where she was tied up. For years the huge steel-plated boiler which crashed through the Victoria’s hull, rested on the river bed beside her. Several generations of small boys used it as a diving tower while swimming.

On June 1, seven days after the VICTORIA capsized, Coroner Dr. J. R. Flock assembled a jury to enquire into the disaster. The case for the jury’s consideration was the manner in which Fanny Cooper met her death. Incredibly the verdict did not mention Fanny Cooper nor any of the other victims. Instead, the jury parceled out responsibility for the wreck to Captain Rankin, george Parish, the VICTORIA’s engineer and the Steamboat Inspector who passed her as fit.

In part the verdict read “We do find that the capsizing of the steamer VICTORIA was caused by water in the hold. We believe this water leaked from a hole in the bottom from some unknown cause. We suppose that this injury was caused by coming in contact with a stone or snag in the river. (At the time of the wreck, Captain Rankin said the boat jarred just before she capsized. Subsequent examination of the raised hull confirmed that the hull had been punctured.) We are also convinced that the boiler was not securely fastened and that the stanchions supporting the hurricane and promenade decks were too slender and made chiefly of pine and not properly braced.”

The jury found the ship’s engineer guilty of neglecting to inform Rankin of the boat’s condition. Rankin, too, was censured for not inspecting his boat before leaving Springbank. But in both these criticisms the jury overlooked testimony which proved that Rankin as captain, was well aware of his ship’s condition: he had refused to sail with the overloaded ship until ordered to do so by Parish. In his turn, Parish was criticized for not hiring a wheelsman. The jury felt this lack took Rankin’s full attention from the safety of his ship and passengers. The steamship engineer was found at fault for his inspection of the boat.

The verdict found little favor with the press. One of the sharpest criticisms came from a Toronto Globe editorial: “The verdict of the coroner’s jury is by no means satisfactory. The death of Miss Cooper was entirely ignored and it is impossible to discover whether the jury believed she perished as the result of carelessness or negligence of individuals. The capsizing of the boat is said to have been caused by water in the hold, a finding that in our opinion is very ill-supported by the evidence.”

As Rankin and Parish were leaving the courtroom, they were arrested on charges of manslaughter but released on $3,000 bail each. The case came before the Middlesex Grand Jury at the fall assizes which opened in London on Sept. 10. On Sept. 22, the grand jury handed down its verdict: it refused to indict the two men. Rankin and Parish were freed.

Almost overlooked at the time was the most curious aspect of the whole case. It concerned the inspection of the VICTORIA and the subsequent issuance of a license for her operation as a passenger-carrying vessel.

On May 22, 1880, while Captain Wastie was still operating her, the VICTORIA was inspected by a government man from Toronto. Wastie was given verbal clearance permitting him to sail for the season. Through a governmental mix-up, the actual certificate of seaworthiness did not arrives until October of the same year although the expiry date was clearly marked as May 22, 1881-two days before the disaster. By the time the license arrived, Parish had assumed control of the boat.

On the morning of the wreck, the collector of customs at London approached Parish at the city docks and demanded to see his license. “I have it at my home but I assure you it is in order,” Parish replied. Later, his defense was that he assumed the certificate was good for one year from the time he had received it; he thought it expired in October 1881. Was Parish honestly mistaken about the license or did he know the facts and ignored them ? The Coroner’s Jury made no effort to find out. But the plain truth was staring them in the face: When the VICTORIA, loaded with six hundred passengers went down with the loss of a hundred and eighty-one lives, she was sailing illegally.

– Stanley Fillmore, Maclean’s Magazine

A plaque was later erected near the site of the disaster.

Article originally found here.

“Disaster To Steamer Victoria At London”

At London Thames is a broad stream,

Which was the scene of a sad theme,

A fragile steamer there did play,

Overcrowded on a Queen’s Birthday,

While all on board was bright and gay,

But soon ‘neath the cold waters lay,

Naught but forms of lifeless clay,

Which made, alas ! sad month of May.

– James McIntyre

You must be logged in to post a comment.